Home Page

Recollections of Robert Ballantine, W8SU

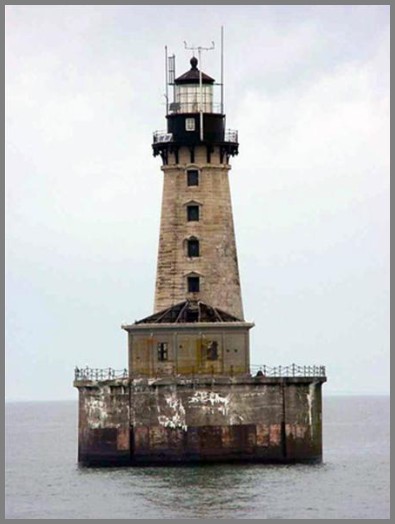

THE STANNARD ROCK

INCIDENT

OR ASSISTING AT THE LONELIEST PLACE ON EARTH.

Stannard Rock photo by USCG |

The year was 1961 and your writer was a radioman serving aboard the Coast Guard Cutter Woodrush. The Woodie (radio call NODZ) home ported in Duluth, MN. She was a 180 ft ocean going tender, on regular early summer aids to navigation duties out in Lake Superior. The crew numbered 50 officers and enlisted. We had the average radio traffic workload, departing port, mainly removal and setting of buoy navigational aids and resupply of light stations. Additionally with regular administrative and search and rescue duties, the "Woodie NODZ" made a cozy billet for a single radioman who liked CW! As I look back now CW actually was the only thing we could count on to get thru. Considered better duty, due to a one-watch radio billet. I ran the daily watch 0800 to 1200 shift and return for four hours between 4 PM to 8PM. We had no electronic technician aboard so the mundane problems fell on my shoulders which I didn't mind at all. Bridge equipment, PA system, recreation radios and speaker amplifiers in officers' country, crews mess and Captains quarters. Antennas were checked and maintained and, when in port, quartermaster gangway watch duty plus duty mail orderly. Overall, it was nice duty, but OH! those cold winters in Duluth! |

|---|---|

The radio room equipment aboard the Woodrush was not working well, and

the ailing HRO receiver with plug in band coils was a design out of the

1930s that had been tinkered with by many radio men prior to my

arrival. This combined with the T-106 Mackay built two hundred watt CW

transmitter that was inoperative, made life very difficult in the radio

shack. I was using my amateur radio transmitter, a Johnson Viking

Ranger on a 4337 KHz crystal on the only District Nine CW channel. It

would put out a grand total of 25 watts into the very short antenna

system the buoy tenders used on the mast and to the after portion of

the vessel. In the map room between the bridge and radio room, was an

unused humongous HF radiotelephone system with dozens of banks of

relays owned by Lorain County Phone System, inoperative from day one.

The radar system seemed to work flawlessly.

Communications on Lake Superior are vastly different than on land and

not what one would think to be the norm. We were using HF only and

before VHF was installed in C.G. vessels. Words cannot easily describe

how difficult communications can be at times on Superior. Earlier radio

conditions were chronicled by the radiomen who formerly worked on the

ore carriers. They told of awful H.F. Short Wave radio conditions in

Superior, it was as if there was a steel door blocking communications

from west to east on the lake. Propagation was very poor out near

Duluth Minn. Some thought it was the iron ore in the region, making it

very difficult to raise the Soo from the far western end of Superior.

AM radio was difficult too and the stations that came on AM radio

consistently were stations from the Gulf Coast and Texas.

Our usual guard was handled by NMP at CG Secondary Radsta Northbrook,

IL. Meaning all communications would go through them, in Illinois. At

various times, NMD at Cleveland would chime in and take a message or

two to keep busy. Normally NOG secondary radio at the Soo was not heard

at all from Duluth the far western end of Superior. It was not until we

got in the vicinity of Whitefish Point that NOG, Sault Ste. Marie, MI,

would come in steadily to have good communications. NOG had a very

directional pattern. After viewing the installation at the Soo, I then

realized that their setup was very hastily conceived but favored

northern Lake Huron and parts of Lake Michigan. They utilized an

end fed vertical wire, leading up on the side of a 80 foot pine pole at

the waterfront station dock side viewing "The Sault Canal Army Corps of

Engineers operations." To add to the problem they ran only 300 watts

output to that system which was very under rated for their duties. It

made your radioman very proud to be able to get a radio message back to

land due to those trying circumstances.

We left the seclusion of our Duluth berthing, the second week of June

1961 for what turned out to be a particularly bad trip, working the

Aids to Navigation - Apostle Island Group. Nothing seemed to go right,

rough weather made it difficult to set and remove buoys. Radio

conditions were even worse, lots of rain static and arcing in the

antenna system would fry in the speaker for hours on the radio set.

The evening of June 18th 1961 would evolve into loss of life for

Stannard Rock Light Station personnel in Lake Superior, vicinity of

Marquette Mich. 50 miles off land. A small Coast Guard crew was

attempting to automate the light thus saving a considerable cost to the

government. Automation was a trend that was starting to catch fire and

which would change the old ways forever in the Coast Guard.

A propane explosion ripped through the machine room attached to the

light tower, killing Guardsman William Hamilton outright. Three

personnel had various injuries and were stranded on the granite base

three days before a passing ship noticed them and notified Coast Guard.

Coast Guard Radioman Gene Small at NMD, Cleveland advised me many years

later (2000) when he realized I was the CW operator aboard the

Woodrush, the night of the Stannard Rock Incident: "The Woodrush NODZ

was underway near the north entry to the Portage Canal, AKA Keweenaw

Water Way. That night we couldn't raise you on the radio." We were

having one of those Ohio lightening storms that made you want to not be

operating one of the transmitters and couldn't hear much. Both

Secondary Stations at the Soo and Northbrook were helping us listen,

but nothing we did seemed to wake you. So, in desperation, I did the

unthinkable, I first put the 15B on MCW and when that didn't work, I

turned on both the TCC4 and the 15B and called the Woodrush on 4 megs.

The sound you wouldn't believe. Gates Mills, Mayfield, Lyndhurst, even

over in Willoughby people were calling the police to find out what was

happening to their TV sets. The District Office, SAR Center, took their

phones off the hook for a while till they would stop ringing. One Lady

told the Gates Mills police that I blew the tube right out of her TV

set. She lived over on Mulberry." By the way a single FRT-15 is capable

of five thousand watts output.

Coming up on schedule from the Woody next morning, I (Ballantine) had

copied the operational immediate message from Cleveland HQ before me

and disbursed it to the bridge for their action and signature. We

ran as hard as the old diesel 180 footer could go (13 Knots) maximum

speed, arriving at Stannard Rock approximately 3 or 4 hours. Coast

Guard Air had removed the victim and part of the renovation crew,

administering first aid, leaving food, water and blankets. All that

could be seen was a demolished block equipment building, a coal pile

that was in shreds, several acetylene tanks in the rubble. The light

structure seemed ok and still standing. Needless to say the

construction crew was eager to get off the rubble and get food and hot showers.

Stannard Rock Light Station was called at one point, "The loneliest

place on earth." Jutting out into Lake Superior fastened upon rock

ledges, reeks with the lore and danger of Lake Superior. Its namesake,

Charles Stannard, Captain of the schooner John Jacob Astor, discovered

this under-water mountain in 1835. The mile-long reef lies just beneath

the surface of the water, in a major shipping lane 50 miles offshore

from Marquette, Michigan. It was first lit in 1882, and is considered

one of the top 10 engineering feats in the U.S.

Over the years I had forgotten how difficult communications could be on

Superior and wished that somehow I could have gotten immediate word

when our assistance was needed. However, with split shifts, poor

weather and equipment, it was just no ones fault that we weren't

dispatched immediately. The bridge personnel aboard were glad when I

came on board as radioman because they had an awful time on radio phone

transmitting voice messages, before my assignment to the ship. While

underway they had a continuous 2182 KHz distress watch and could have

easily picked up the information had conditions been better, but it

just wasn't possible that night. Many times, I would be rousted off the

mess deck or out of quarters to report to the radio room for messages.

The 2182 KHz calling and distress channel did work as specified however

not under severe weather conditions.

As a result of the tragedy, the Stannard light was automated in 1962.

Today, a 300mm plastic lens shines from Stannard's solar powered

lantern. Satellite communications makes available wind and weather

conditions on the Internet. After Stannard's automation the original

2nd order Fresnel lens, damaged by the 61 blast was packed into 5 large

wooden boxes and then went missing for over 30 years. In 1998 the lens

was discovered in storage at the CG Academy basement in Groton, CT. In

1999 the lens was returned to Lake Superior and is on display at

Marquette Maritime Museum.

Approaching storms traveling up Lake Superior build up incredible

intensity before slamming into Stannard Rock Light. After the rock was

automated, a maintenance crew got trapped in the lighthouse for days in

a sudden storm. Gale winds slammed tons of ice against the tower and

platform and when it was over they were trapped by 12 feet of ice.

Taking two more days of chopping to free them.

The Woodrush got its name from bushes and shrubs which were the

standard buoy tender names selected by the Coast Guard in the 1940's.

After 35 years of service from Duluth the Woodrush was retrofitted and

reassigned to Alaska where it served until 2001. The Woodrush, then

WLB407, was decommissioned 2 March 2001 at Sitka, Alaska and given to

the little African Nation of Ghana. For two weeks, Woodrush crew

members trained 12 members of the Ghanian Navy in the operation of the

ship. Cutter Woodrush, its crew and the Ghanaian Navy crew sailed the

ship to the Coast Guard Yard in Baltimore before transferring it to the

Ghanian crew. So the Woodrush lives again to serve and sail around the

Atlantic African coast. Another new class buoy tender made in the Great

Lakes arrived for duty replacing the Woodrush.

We had some memorable times on re-supply to Rock of Ages in Superior at

Isle of Royale. It was an unusually shaped light house affectionately

called "The Spark Plug." It was a difficult area and we had to stand

off safely near by. Weather was usually windy and cold. The folks

stationed at these places earned their pay and were taken off station

in the winter months. All these lights are automated now.

I recall a few incidents that were memorable off duty working the ham

bands. On 40M AM some of the Lake Freighters and Ore Carriers had hams

aboard, one of them was Moby Dick K80DY/MM He was quite a gentleman and

always had someone on the hook to chat with. He was a shipboard

engineer and had plenty of time to play with ham radio. I would work

Dick going thru the Soo Locks and then downward out of the St. Mary's

River, they would be enroute to Rogers City for more crushed rock and

cargo.

After 41 years, I have had the time and ambition to write this story, I

hope anyone reading it can feel a sense of what really happened and how

difficult it was servicing these lonely places on earth and the folks

who maintained them.

Bob, W8SU

Summer 2006

Reconstruct the e-mail address: pfpalm at nlcomm dot com

Back to the Radio Officers Page